When my parents were kids, they’d play outside after school or on the weekends. When I was a kid, I played games on the family PC. These childhood experiences shape us, for better or for worse.

Somehow we ended up discussing video games. It was probably the last topic I ever thought to raise within a 10 feet radius of my friend Emil, a boxing trainer. He absolutely loathes gaming – time is much better spent at the gym, he says.

I am inclined to agree. Especially when I look around and see what young men have grown up to become as a result of those pesky, addictive video games – boring guys who lack patience and perseverance, have poor social skills and no real hobbies.

But as much as Emil and I are on the same page when it comes to the bigger picture, namely that video games stunt development, I believe there is a fringe case to be made.

Slice of life

I have spent literal years gaming. The amount of hours the average gamer spends in the digital sphere may lead you to question if games are not just a massive, addictive time sink. To that I say: probably. A glance at the above numbers suffices to realise how many (more useful) things I could have been doing with my life. But boy, must I admit, games can be fun.

Simultaneously, it would be disingenuous if I said that games are a complete waste of time. While positives are scarce to be found, the ones that do exist deserve pointing out. And fear not, I am not going to conclude this post with ridiculous suggestions like “have your son play CounterStrike for 3 hours a day so he develops good hand-eye coordination.” If that is something you truly care about, go play some tennis or volleyball together. Alternatively, sign him up for the shooting range, maybe one day he’ll become the next Yusuf Dikeç.

Enough said, let’s dive straight in.

Emotion and Analysis

My friend Michael is a nutcase. If you saw him, you might mistake him for a bouncer with a strange taste in music. Just picture a buff guy sitting behind the wheel blasting out a Broadway musical. He is probably the last person you’d expect to be a former top 200 StarCraft II player. But nothing is less true. In a recent conversation, he provided this insight:

“Emotion in a competitive game is terrible. It is something you need to shut out, because if you’re emotionally attached to anything in a video game you will never climb or progress.”

He is not the first to point this out to me. I am reminded of a certain summer holiday (2013, I think), when I went to visit Menno, one of my high school buddies. I spent around 5 days at his place watching movies, playing Skyrim and browsing Reddit.

At the time, he was pushing for Challenger rank (top 500 in Europe) in League of Legends. I watched him play for hours on end. What made observing him so interesting was his emotional restraint and strong sense of self-accountability. Stoically, he analysed every possible angle, thinking of new ways to improve his own gameplay. This stood in stark contrast with everyone else (or people in general), who imminently point fingers in all directions when something does not go according to plan.

Even if we’re talking about just a video game, most people will consider themselves last to blame.

“What was peculiar about Menno is how much time he spent watching replays of his matches.” – I related to Michael – “This is something nobody does. Everyone rather forgets and launches a new match instead. Only to repeat the same mistakes, I guess.”

He replied:

“Oh yeah, I also watch my replays all the time. The moment my match ends, I hit replay to see where I fucked up.”

Quality over quantity.

Unique to gaming is the ability to go back in time and do deep analysis. But the more important benefit is that the virtual world gives more direct feedback than the real word.

Cuss at your teammates, and they might disconnect from your game, leaving you to your own devices. Meanwhile, in real life, everyone rather keeps quiet about your shitty behaviour. In an environment where anonymity is ubiquitous, all social constraints from people to express their true thoughts are removed. Somebody telling a fellow player to drink bleach only because they forgot to press a button is a mainstay in multiplayer games.

Imagine the social backlash if somebody said that out on the street.

But toxic gamers are not always such a bad thing. Michael explains:

“To get better you need to be able to shut out ego and take ‘asshole advice’ from one-tricks1.” The reason these one-tricks are often lower rank is because they lack versatility:

“That low rank Riven2 player may suck at execution, but in a vacuum he will beat players ranked much higher.”

Some people may indeed act like assholes, exorbitantly flaunting their skills. You can let them get to your head, or perhaps better suck it up and learn from them.

Dependence

If I told you an online game saved thousands from starvation, you would probably think I’m making shit up. But it’s a true story. In the 2010’s, the Venezuelan economy started collapsing. Inflation caused many to be unable to afford basic necessities. Some tried finding gigs online that paid in a more stable currency. One example of said gigs was playing Old School RuneScape – people essentially played a video game and switched their in-game pixel money for real dollars.

As much as it’s a cool story, I need to point out that what these Venezuelans were doing is illegal. Real World Trading (RWT), or switching online currency for real money is against the rules. This points to a bigger problem, namely that the real value of anything in a game depends on not just the game’s economy and players, but also hinges on the developer’s final decision. If the maker of the game is not okay with something, they can simply eliminate it with the press of a button, and you’ll have nothing to say about it. The Venezuelans had little to lose, thus elected to take that risk. Unfortunately, many of them found out the hard way that they were playing with fire; they had their accounts banned or their wealth removed.

It is a bitter reminder of the fact that you can lose anything you possess in a game in an instant. Another of such examples is Riot Games’ Vanguard, an anti-cheat programme operating at kernel-level (i.e. it has access to everything on your PC). The announcement sparked major community backlash. Many players felt betrayed, and argued that it had been Tencent, a Chinese shareholder of Riot Games, who had pushed Vanguard through. The update instantly wiped out the entire Linux player base. Many others (including myself) feared for their privacy and uninstalled the game as well. Removing the game implicitly meant forsaking the time and money we had put into it, whether we liked it or not.

Then again, at the end of the day, losing access to the skins you purchased in a game (or any other form of pixels, for that matter) is less damaging to the soul than losing your house, your money or your friends. And that is probably a good thing, because maybe, just maybe, those experiences will teach you to value the real deal over your fake house, your fake money, and your fake online friends.

Language

Without video games, I would not be writing this article. The reason is simple: gaming taught me English. From age 10, I spent over an hour a day roaming the world of RuneScape, learning the language on the fly. That was a year and a half before I had my first ever English class. No wonder I didn’t learn any English in school.

Any half-baked linguist will tell you that the best way to learn a language is to immerse yourself. Wanna learn Portuguese? Move to Brazil (unless you prefer the less intelligible version, then move to Portugal).3 Most people, however, cannot afford to move to another country simply for the sake of learning an extra language.

Enter video games.

Games will outclass any school teacher. Any game featuring an open world does wonders for vocabulary. On top of that you get to interact with native speakers. The immersion a game offers is simply unparalleled. Just remember not to bother with languages other than English. Such games do exist, but they are scarce (plus half the time the translations are actually scuffed). There may be one exception to this rule, as illustrated eloquently by Aaron Clarey in his book Worthless:

“Rennt um eure Leben, er hat ‘en panzerfaust!”

Yeah, that right there cost me $1,200 in tuition back in the 1990s. A degree in foreign languages will certainly cost you more. Spend your money instead on WWII video games. You’ll learn a lot more German and it will be a lot more fun.

The only thing games usually fall short on is listening exercises. I know plenty of gamers who learnt English very well, but their accent is awful.

What saved me was television: I watched Discovery Channel and National Geographic for 3 hours a day from age 12 to 16. The result is that my accent is a weird amalgamation of American and British English (thank you Mythbusters & Brainiac).

Kids copy what they hear. Some US mothers found this out the hard way when their children developed a British accent from watching a cartoon. How elated they must have been when justice was served a few years later.

Case in point, imitating is the most effective way to learn, don’t waste your time at school.

Economics

In high school I had an Economics class. It was almost as useless as English class. Every time I sat there listening to my teacher explaining how the market works, I thought to myself: “Nothing I haven’t seen before.”

And I’ve seen – or should I say, been through – a lot. From that one time where I, aged 13, ran down the stairs crying after a scammer took all my virtual savings, to that time when I gleefully waddled around in Path of Exile for two weeks wearing a helmet I had crafted, before accidentally discovering it was worth twice as much as everything else I owned combined.

The highs and the lows – I have seen it all. No high school teacher, through no fault of their own, is going to open my eyes any further.

To demonstrate how economics in a video game taught me “real life economics”, here are some examples taken from the game RuneScape4:

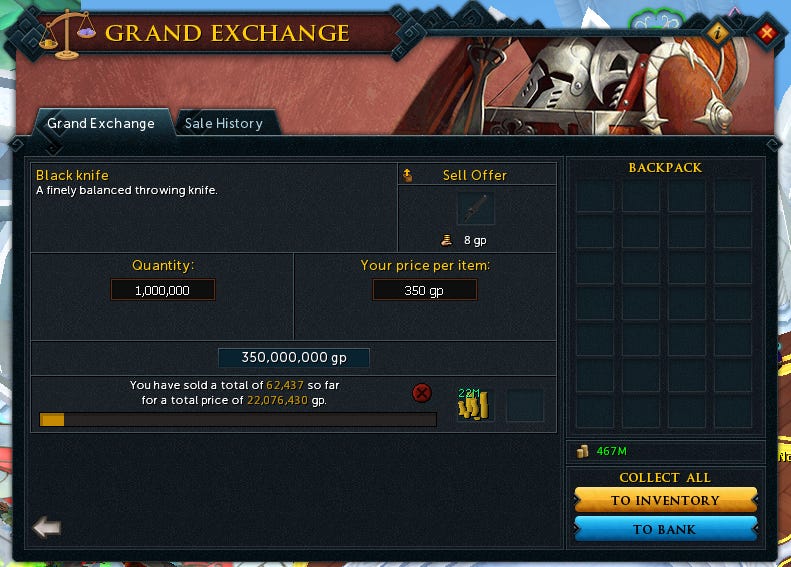

The above picture represents what players refer to as “flipping”. This is the game equivalent of the principle of “buy low, sell high”. Through trial and error, I found that, just like in real life, in-game profitable items often are:

expensive (e.g. high tier gear)

comparable to: cars, real estatediscontinued (e.g. holiday rares)

comparable to: old Nintendo games, vinylstraded in low quantity (e.g. situational / quest items)

comparable to: spare car parts, pianos

The common denominator of the above items is that either the number of products themselves and/or the possible traders are limited:

expensive items: few people can afford to trade them

discontinued items: with supply cut off, few items remain to be traded

items traded in low quantity: few people are interested in owning/trading

Just like in the real world, to be a successful trader you need to know how the market works, starting off with basics such as Supply & Demand. If you fail to do so, as I have many times in the past, you will inevitably lose money. Thankfully, it was only virtual money I lost in this learning process. Incorrectly reading a virtual market and screwing things up is the video game equivalent of investing in a company you know nothing about; a recipe for disaster5.

One of my most profitable long term ways to make money was my method of “crafting Godswords”. Here are the factors that contributed to it:

it is a multi-step process, thus harder to discover

the method requires buying 4 different components, disincentivising people to give it a go

components are undervalued

the end product is overvalued

The result: a massive margin between the costs of the components and the end product.

Perhaps the above scenario sounds oddly reminiscent of a production cycle, in which every party involved takes their cut. Here, however, you do the entire process yourself, meaning you get to take all the cuts.

I did something similar with “Crystal staves”, which entailed creating a highly desired item out of thin air and 200.000 gold pieces.

And if you want an example of how prices can fluctuate, let me introduce to you my 1 million black knives:

Psychology

If you read between the lines of the previous paragraphs, you will find that people in general:

harbour many unexpressed feelings inside

love flaunting their achievements

are dependent on others

are lazy

While that sounds like a grim picture of humanity, it’s perhaps not the most accurate at surface level. After all, in games people often let themselves go. All the frustration they kept inside while working their day job comes out when they place themselves in front of their laptop screen.

Without exuding any more game apologetics, let me mention a few more parallels I have observed of the contrast between people’s behaviour in games and in the real world. I have seen:

conmen from A to Z

a fair share of gambling addicts

people succumbing to peer pressure

money being treated as a power tool by the extremely wealthy

players making obscene amounts of money and squandering it within the span of a day

Obviously there are the lone wolves, those who play for pure enjoyment, and some who love helping out newbies. But these are the kinds of people who keep quiet, while the crazy, the wealthy and the downright evil attract the most attention.

That is why you should take neither games nor reality too seriously if you want to live a happy and peaceful life.

Games offer a glimpse into how people interact. The analogy is similar to Jesse Silverberg’s TED Talk “Moshing with Physics”, where he compared atom movement to people dancing at a metal concert. His conclusion: if you want to predict how people behave in chaotic situations (e.g. building on fire, explosion), go watch a metal music festival.

The same is true for games. Some can teach you analysis, language, economics, concepts like leverage or how the average human thinks.

One might say then, that giving games a chance means that we bring out some more authenticity and the opportunity to learn something useful about life; it also doesn’t hurt if we were more observant with the subtext of ordinary life.

One-trick refers to somebody who is extremely good at one aspect of the game, for example, the gameplay of a single character.

Many perceive Riven to be the most mechanically intensive character to play. She has over 50 unique “animation cancels” that expert players utilise regularly to boost their gameplay.

At least based on the limited insight my friends, Pablo Vallejo, Lukas Piccini and Eduardo Frigatti, were kind enough to provide me with.

All the examples are my own, except for the Webweaver Bow, which was submitted to me by the astute Michael “Galaxybrain” Murphy. His flip is from Old School RuneScape, which has an almost identical market system to RuneScape 3.

Pun absolutely intended for the fellow (ex-)(Old School) RuneScape players.